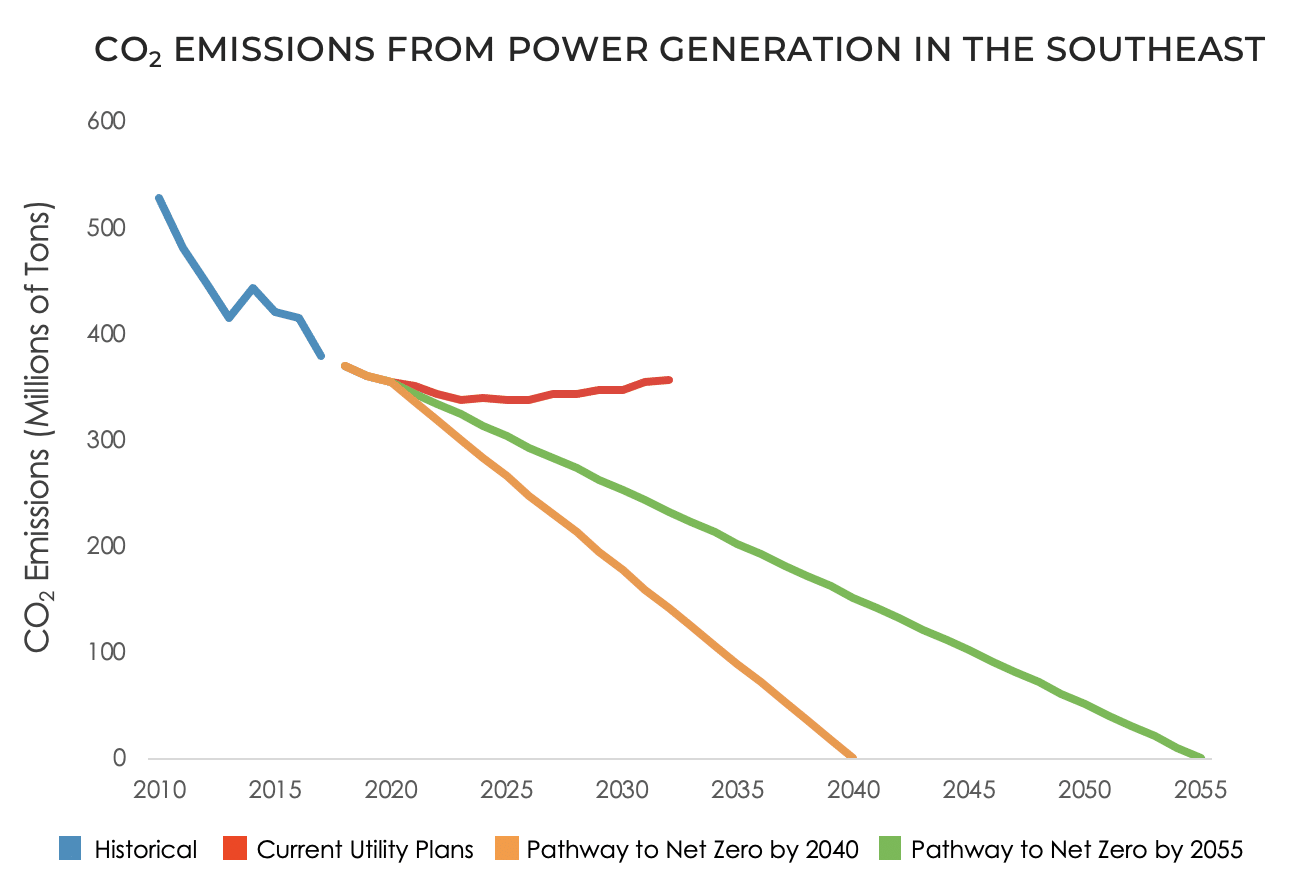

There’s a growing consensus from customers, investors, and regulators: everyone wants a carbon-free power supply from electric utilities. However, scientists have been clear that decarbonizing isn’t really a want, it’s a need. Climate scientists tell us we need to get to net-zero global greenhouse gas emissions between 2040 and 2055 at the latest to limit global average temperature increase to 1.5 degrees C and avoid the worst of the climate crisis. Many utilities and municipalities are beginning to acknowledge that dynamic, but our second annual report, Tracking Decarbonization in the Southeast: Generation and CO2 Emissions, shows there’s still a lot of work to do before any of them are on track to reach net-zero.

Download the Report

Read the Report Series

Watch the Webinar

Why do we care about decarbonizing the power sector?

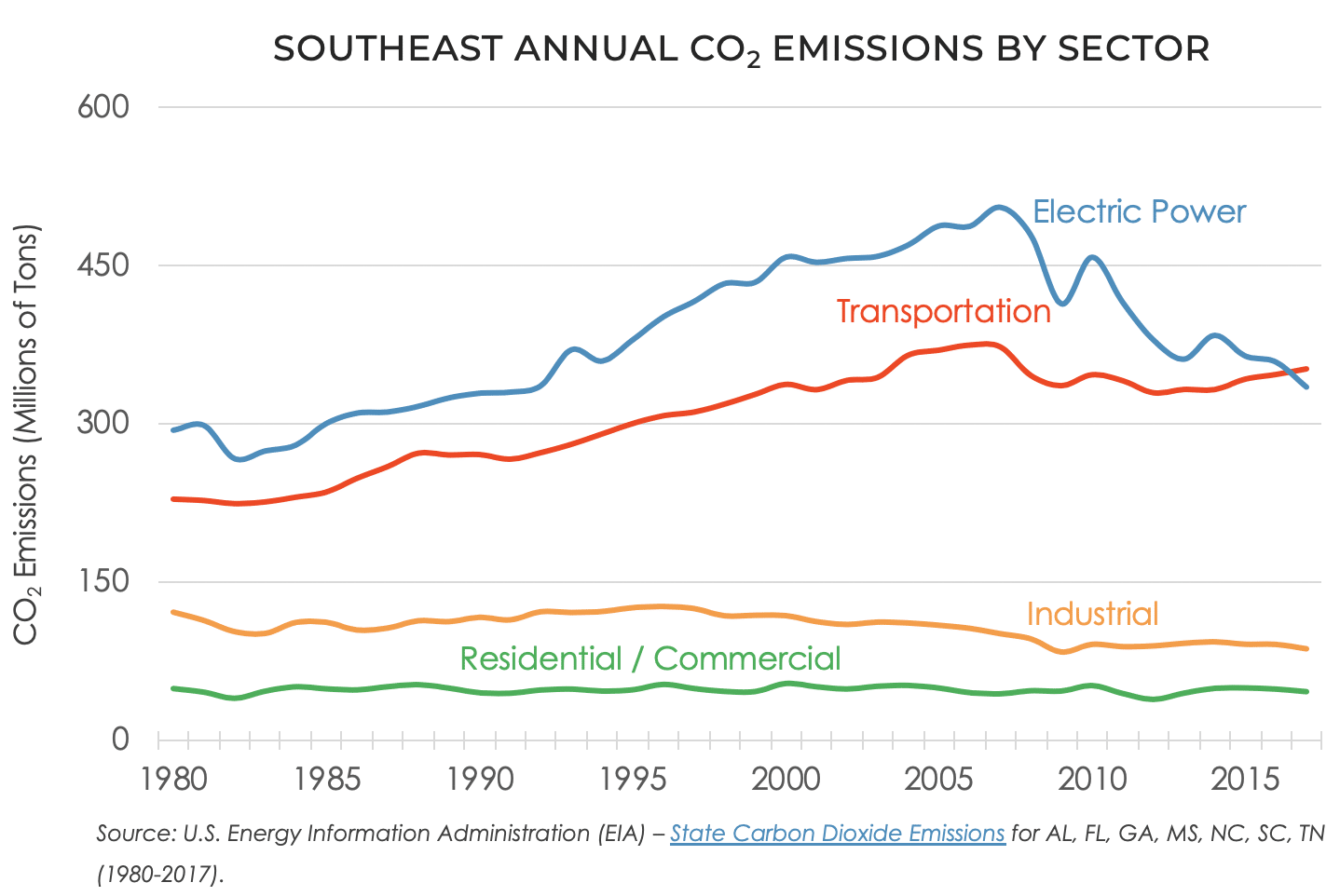

CO2 emissions are reported by the end-user, the sector where fossil fuels are ultimately consumed, to measure how each one contributes to overall greenhouse gas emissions. Typically, sectors are broadly categorized as electric power (utilities), transportation, residential, commercial, and industrial (but if you’ve ever read the national greenhouse gas inventory, you’ll know that there are an incredible number of subcategories within these larger ones).

Globally, emissions are on the rise. But on a national and regional level, reported annual CO2 emissions are beginning to drop. The primary driver for this decrease is observed in the electric power sector, which is the focus of our annual report. However, one notable result of falling emissions in the power sector from their peak in 2007 is that the transportation sector has surpassed the electric power sector as the largest regional source of CO2. Essentially, utilities are decarbonizing and emissions from transportation are growing.

However, the fact that transportation has eclipsed the power sector does not diminish the importance of decarbonizing the power supply. In fact, this still holds a lot of significance for utilities in the Southeast, as more consumers, businesses, and local governments are beginning to drive electric. When electric vehicles (EV) are plugged in to charge, they’ll be using utility-generated power for their transportation needs. Therefore, the cleaner the electricity, the cleaner the EV.

Are decarbonization goals the new norm?

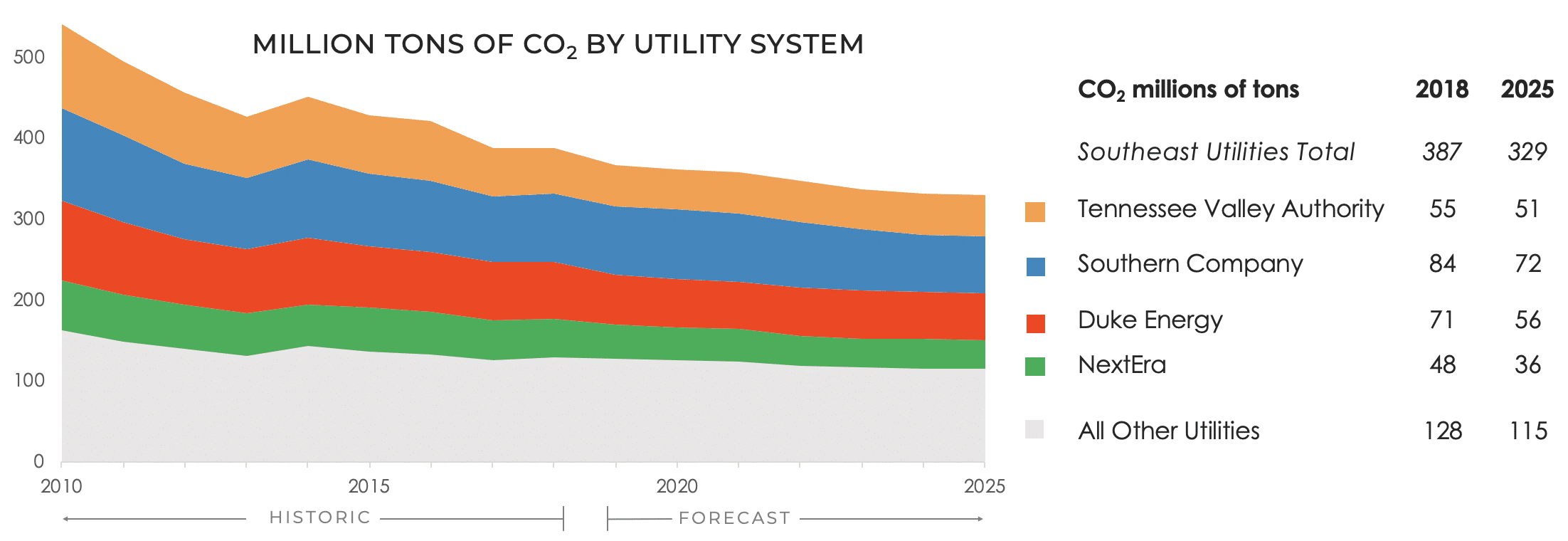

The Southeast is home to some of the biggest utility systems in the nation, some of which have been in the national spotlight for establishing decarbonization goals. Duke Energy, Southern Company, NextEra Energy, and the Tennessee Valley Authority (TVA) are responsible for approximately 70% of emissions from power generation in the Southeast. Of these, the two largest CO2 emitters, Duke and Southern, have both made pledges to reach net-zero emissions by 2050, while NextEra has an emissions rate goal equivalent to a 40% total emissions reduction. TVA has made no formal commitments (though it has publicized expected reductions to which we reacted to in a different blog).

There’s also a very promising swell of interest in decarbonizing from state and local governments in our region. Throughout Florida, communities have formed regional resiliency coalitions of local governments, which have lead to numerous climate commitments. And earlier this year, the state House in South Carolina passed a resolution to transition the power supply of state-owned utility Santee Cooper (or its successor if it is sold) to 100% clean energy by 2050, although the session adjourned without a decision. In Tennessee, the Mayor of Knoxville has formed a Climate Council to develop a plan to help the city meet its goal of reducing carbon emissions by 80% by 2050.

The styling of these targets all differ a little (net-zero, low to no carbon, carbon-free), but two things remain key: The first is the 2040 to 2055 timeframe because we need to get to net-zero global greenhouse gas emissions during that time to avoid the worst impacts of the climate crisis. The second is the reduction in total CO2 emissions versus an emissions rate. That might sound like an arbitrary distinction to some people, but using NextEra Energy as an example, a 67% reduction in emissions rate actually equates to a 40% reduction in annual emissions. A lower emissions rate is a great start, but to align with the levels set forth by the science, decarbonization goals must focus on total reductions in a timeframe that goes beyond that of the typical planning horizon for utility resources plans. Speaking of which…

Utility plans miss the mark

Utilities in our region use integrated resource plans (IRPs) to create long-term plans outlining which energy resources they will use in the coming years (IRPs are also one of the many acronyms energy advocates entered into an arranged marriage with). Unfortunately, current IRPs by utilities in the Southeast fall short of the emissions reductions recommended by scientific guidance, so unless utilities make significant changes to current plans, the Southeast will not be able to stand with the rest of the world in preventing the climate crisis.

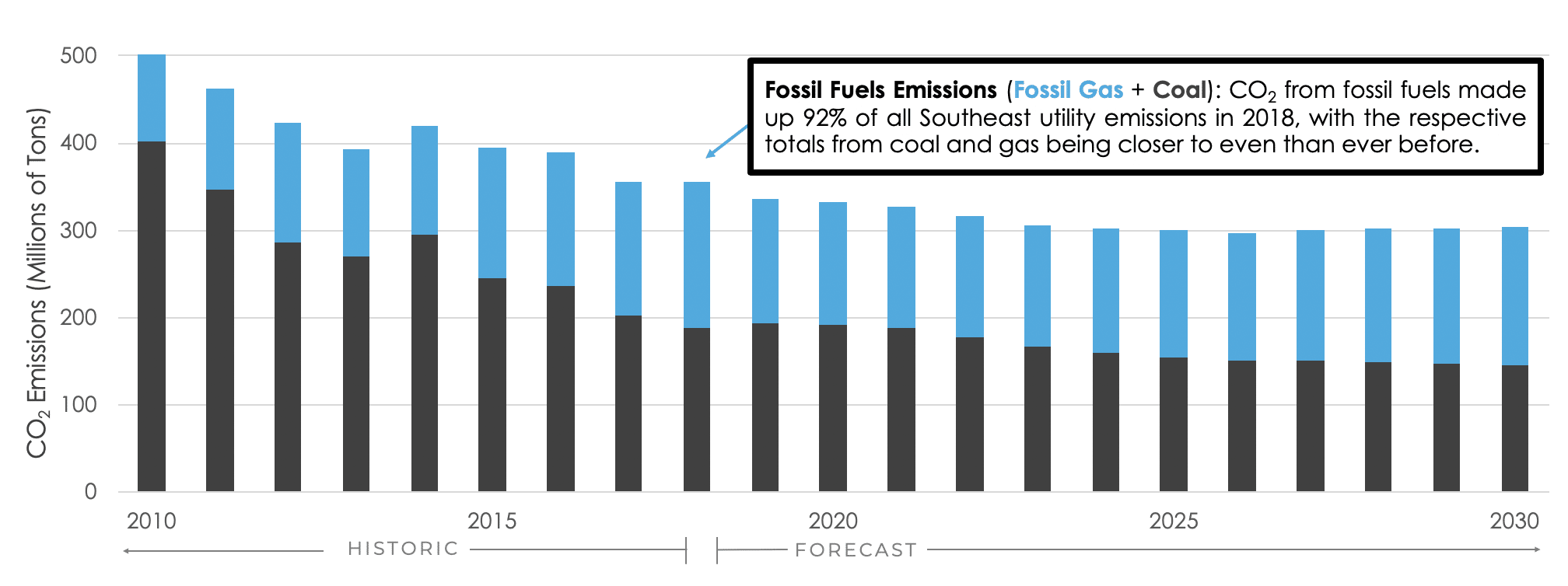

The emissions impacts of current utility plans shows that business as usual isn’t going to cut it and that there’s still a lot of work to do be done before any utility is on track to reach net-zero. Unfortunately, current plans still include significant fossil fuel usage through at least 2030. Although the latest utility plans include some new solar generation and energy efficiency investments, fossil gas remains the go-to new power plant for utilities in the Southeast when retiring coal capacity. In fact, the region is now at the point where the annual amount of CO2 from fossil gas plants is nearly even with coal plants.

SACE acknowledges that some utilities have managed to reduce emissions from older power plants by fuel switching from burning coal to fossil gas, but the increase in generation from burning fossil gas will make it difficult for the regional emissions rate to continue to fall below that of an average fossil gas plant in the future. In short, replacing coal plants with even larger gas plants isn’t going to get anyone to net-zero!

Today, as some utilities are updating resource plans, this continued investment in fossil gas infrastructure is particularly troubling. Many resource modeling practices used by utilities during their IRPs make it difficult to select anything other than fossil gas for new generation, devalue the importance of demand-side measures like energy efficiency, and do not implement best practices like all-source procurement for new supply resources. Another issue is that utilities frequently tout fossil gas as a “bridge fuel” to minimize the fact that they’re still burning fossil fuels.

Luckily, there are always new opportunities on the horizon. Some utilities in Mississippi are in the process of conducting their very first public IRPs. Duke is on the eve of releasing what could be a high-profile resource plan in North Carolina, where Duke has been specifically asked to evaluate retirements for all remaining coal plants and take the state’s emission goal into account. In our next blog, we will dive deeper into how Duke and the other major utility systems in the region compare. Can’t wait for the next blog post? Download the report below and read about each utility!

[button color=”blue” url=”https://bit.ly/SEEmissionsReport2020″]Download the Report[/button]

[button color=”blue” url=”https://cleanenergy.org/?s=SEEmissionsReport2020″]Read the Report Series[/button]

[button color=”blue” url=”https://cleanenergy.org/news-and-resources/webinar-tracking-decarbonization-in-the-southeast-2020-report/”]Watch the Webinar[/button]

#SEEmissionsReport2020