On November 19, 2021, the North Carolina Utilities Commission (NCUC) issued two orders that could have lasting impacts on the future of renewables, fossil fuels, and energy efficiency in the Carolinas.

One of these orders accepted the short-term action plans that are part of the 2020 Integrated Resource Plans (IRPs), or long term plan for where a utility will source energy from, for Duke’s two utilities that each operate in both North and South Carolina: Duke Energy Carolinas (DEC) and Duke Energy Progress (DEP). This order also directs Duke to make changes to the way it does future IRPs and delays the next comprehensive IRP for both utilities to 2023 so that the focus in 2022 can be on developing a Carbon Plan.

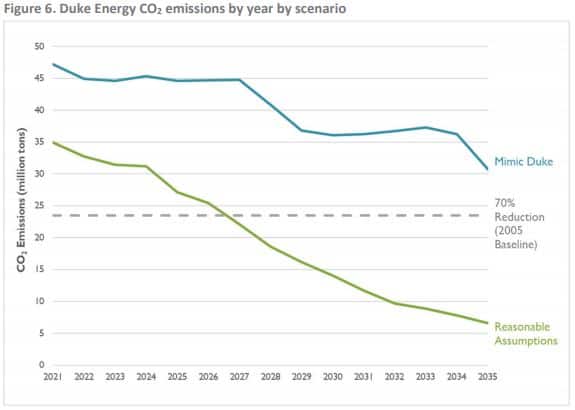

The second order lays out the process for developing that Carbon Plan, called for in recent legislation that passed in North Carolina, House Bill 951. That legislation requires the North Carolina Utilities Commission (who regulates utilities in the state), with input from stakeholders and the utilities, to develop a plan to reduce emissions from electricity generation in the state 70% below 2005 levels by 2030. Duke’s 2020 IRPs already had multiple scenarios that meet these emission reduction targets, and the Duke University Nicholas Institute put out a report in 2020 as part of the Governor’s Clean Energy Plan process that outlines how the power sector could achieve this emission reduction target. Modeling from Synapse Economics consultants shows that using reasonable assumptions for the costs of energy efficiency, renewables, and fossil resources could lead to emission reductions for the whole Duke system (across both utilities and both Carolinas) of 70% by 2027, three years before the target. So while it is ambitious for the NCUC to develop a Carbon Plan by the end of 2022 (as required by HB 951), they are not starting from scratch.

Integrated Resource Plan order

The Commission’s first order (in Docket E-100, Sub 165) accepting Duke’s short-term plan also delays the filing of Duke’s next comprehensive IRP (usually every two years) to September 1, 2023, and provides discussion and guidance on the IRP process in five areas:

- Fossil gas issues

- Method for evaluating the economic retirement of coal units

- Grid impacts of resource portfolios

- All-source procurement, and

- Energy efficiency and demand-side management (DSM).

The Commission declined to accept for future planning purposes the modeling, analysis, and results of the base case and alternative resource portfolios in the two IRPs. Since the IRPs do not identify any resource needs until January 1, 2025, a date at the end of the short-term action plan, the Commission is not approving Duke’s long-term resource plans at this time. Since those long-term resource plans will have to change to meet the Carbon Plan developed in 2022, it really does not make a difference whether the Commission approves the long-term plans filed in 2020 or not.

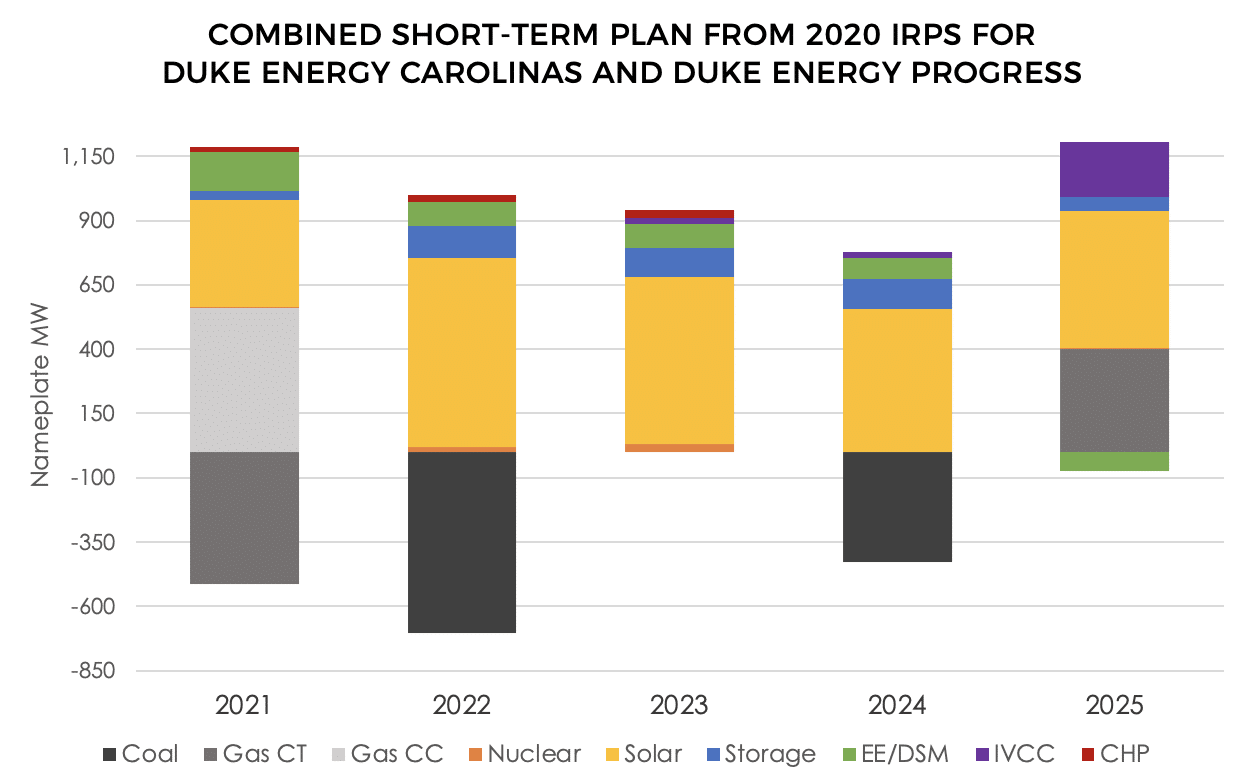

Duke’s short-term plan, which did not change when it filed an IRP update in September 2021, includes the retirement of coal units at its Allen plant and the addition of solar, storage, solar with storage, capacity updates at existing nuclear units, an upgrade to DEC’s pumped hydro storage facility, Bad Creek, and a fossil gas-fired combustion turbine (CT) project.

The Commission provided a discussion of five topics, including some guidance and supplemental filing requirements:

Fossil gas issues

The NCUC responded to testimony about Duke’s abnormal fossil gas price forecast, which used 10 years of “futures” prices, five years of a blend between “futures” and “fundamental forecast” prices, and five years of solely “fundamental forecast” prices. These assumptions likely significantly underestimate future gas prices and open up the risk of customers paying more in the future if Duke continues to increase its reliance on gas (while passing fuel costs on directly to customers).

The NCUC also responded to critiques of Duke’s assumption that gas would be available despite recent cancellations of pipelines. The NCUC directed Duke to use only eight years of “forwards” in future IRPs including a Carbon Plan. More immediately, the NCUC directed Duke to file a supplement to its Base Case with a Carbon Policy scenario and updated gas price forecasts. The new forecasts must use a maximum of eight years of “forward” prices and assumes limited availability of Dominion Southpoint hub gas.

Method for evaluating the economic retirement of coal units

In its 2020 IRPs, Duke made up a coal retirement method that pre-supposes the order in which the units must retire and fails to concurrently consider replacement in the analysis. Since Duke will be utilizing a more capable model in its next IRP, the NCUC states that Duke may continue to use its previous method in the next IRP but it must also use the Encompass model to endogenously determine economic coal retirement dates. This means that the model can evaluate the cost of retiring and replacing each unit in each year to determine the overall least-cost option that still meets reliability requirements.

Grid impacts of different resource portfolios

The incorporation of transmission planning in the IRP was an issue in Duke’s 2020 IRPs, specifically whether Duke should continue to include piecemeal transmission upgrades to its system or look comprehensively and optimize for the entire system. The NCUC Order directs Duke to continue to include anticipated grid impacts in future IRPs, to determine the feasibility of providing a timeline for necessary critical transmission upgrades needed for each portfolio modeled in the IRP, as well as additional related requirements for future resource planning.

Potential use of all-source procurement

All-source procurement was a topic of discussion at the NCUC’s technical conference on Duke’s IRPs, and the Commission comments that they appreciate the discussion. However, since the Commission will be spending substantial time implementing the provisions of HB 951 in 2022, and in light of the significant investment in process design and implementation required for a successful all-source procurement program, they “declined to reach any conclusion regarding how, if at all, and in what ways all-source procurement might be incorporated into the utilities’ future planning processes.” The order leaves this topic open for the Commission to revisit in the future once the initial Carbon Plan is put in place by the end of 2022.

For more on all-source procurement, see our report on best practices or watch the webinar play-back.

Energy efficiency (EE) and demand-side management (DSM)

Duke’s 2020 IRPs fall significantly short of the potential for economic investments in EE and DSM, which lower customer bills and reduce pollution. However, the NCUC missed the opportunity in this IRP order to direct Duke to make significant changes to EE and DSM in future IRPs. Instead, the Commission concludes Duke’s assumptions on the potential for EE and DSM were reasonable and that Duke could continue to use the Total Resource Cost (TRC) test to screen for cost-effective energy efficiency measures despite previous orders by the NCUC that direct Duke to use the more accurate Utility Cost test.

The good news from this order on the EE/DSM front is the NCUC directed Duke to continue to work with stakeholders to implement the recommendations from Duke’s Winter Peak Study.

Carbon Plan process

The NCUC also released a short order (only three pages, in new Docket E-100, Sub 179) laying out the process for developing a Carbon Plan by the end of 2022 as directed by HB 951. Instead of the Commission taking the lead (and in a move that could lead to a delayed and more expensive plan) the NCUC is punting both the stakeholder process and the development of a draft plan to the utility, Duke Energy. Specifically, the Commission requires that Duke hold at least three stakeholder meetings by March 31, 2022, and that Duke file a draft Carbon Plan by April 1, 2022. This is no April Fools Day folks, putting these two steps in the hands of Duke could mean the plan is very likely to overly rely on expensive and unproven technologies like advanced nuclear and carbon capture instead of early and significant investments in tried-and-true energy efficiency and renewable energy. Since the Carbon Plan can be delayed if technologies are not commercially available, the reliance on these kinds of technologies could mean the state ultimately misses its 70% reduction by 2030 goal.

Instead of minimal compliance with the second order, Duke could opt to be more inclusive by holding more stakeholder meetings, allowing full stakeholder participation, and sharing its assumptions and the draft Carbon Plan with stakeholders well in advance so that interactions can be meaningful and constructive. Regardless of how Duke’s stakeholder process runs, entities will have the opportunity to intervene in the docket and provide commentary on Duke’s draft Carbon Plan or file their own draft of a Carbon Plan within 60 days of when Duke files its draft.

In 2022, North Carolina has an opportunity to set itself on a path to decarbonize

To state the obvious conclusion from all of this: the trajectory of North Carolina’s clean energy transition hinges on what happens in 2022. The state could very well accelerate this transition and become a model of driving economic investments and energy efficiency under a regulated, investor-owned monopoly utility structure. It could meet the 70% reduction target early and put it on a path to achieving a zero-emission power sector by 2035. Or the state could choose incremental changes to the status quo, and allow the utilities to prioritize short-term shareholder returns over customer well-being and meaningful solutions to the climate crisis.

We will be engaging throughout the process to push for that accelerated transition. Follow along by signing up for our newsletter and supporting our work by donating today.

#NCCarbonPlan