Over the past seven years, the Tennessee Valley Authority (TVA) has approved an average 50% increase in mandatory fees charged by its local power companies. But if you’re a residential customer on TVA’s system, this information may not appear on your bill, and you may not even be notified when your utility is considering an increase in the fee.

In 2011, as TVA began to cut electricity prices for industrial customers, TVA quietly accepted (or even endorsed) another large change in rates. One by one, about three-quarters of TVA’s local power companies have approved increases in mandatory fees of at least 20%, and in 2018 this will result in a $300 million increase in mandatory fee revenue.

Now TVA is preparing to accelerate the push for mandatory fees in a “reverse robin hood” maneuver. TVA wants to reduce energy charges (rewarding the largest users of electricity) by adding a new “grid service charge” (see slide 67 of this TVA presentation). TVA CEO Bill Johnson is reported to have said that the grid service charge would be 12% of TVA revenue, so it could result in doubling mandatory fees paid by TVA’s residential customers.

While TVA has begun to publicly acknowledge that it has been working on the “grid service charge” concept, TVA has not yet acknowledged that it has already been facilitating a 50% increase in mandatory fees charged by local power companies. As the NAACP has stated, increasing mandatory fees has a disproportionate impact on “low-income, elderly and minority ratepayers.”

TVA Policy Drove KUB to Triple its Fees

Knoxville Utilities Board (KUB) is one of at least 16 local power companies that doubled, or even tripled, mandatory fees over the past 7 or 8 years. In 2010, KUB charged a “Basic Service” fee of just $6.09 per month. Today, that fee is $17.50. KUB has scheduled additional increases so that it will reach $20.50 by the beginning of 2020, which means that over a single decade, the amount customers pay before flipping the switch will have tripled.

KUB initiated this trend in 2011 in response to TVA’s new rate structures. As described in the Synapse Report we released in January, in 2011 TVA began changing the prices it charged its industrial customers, cutting electricity prices paid by industry by 20% while increasing electricity prices for residential customers by 5%. KUB’s manager of rates, Sherri Johnson, explained the new policy (as reported in the Knoxville News Sentinel):

TVA’s new rate structure will include seasonal rates that will change to reflect higher costs of power generation during the summer. KUB is revising its retail rate structure to accommodate these changes, Johnson said. This includes a proposed increase in basic service charges for residential and small commercial customers to be offset by reductions to these customers’ energy rates.

TVA did not disclose that the 2011 rate structure changes would encourage its local power companies to increase mandatory fees for residential customers. Using its arcane regulatory process and lack of transparency, TVA published an Environmental Assessment on its rate structure reform. TVA stated that the purpose of its changes was to “improve opportunities for customers to save money by shifting their power usage from on-peak to off-peak periods (i.e., load shifting).” TVA also claimed that “there likely would be no substantive, disproportionate negative impacts to minority or low-income populations.”

TVA’s rate changes did pretty much the opposite. Instead of improving opportunities for customers to save money, KUB and many of TVA’s other local power companies reacted by raising mandatory fees, which are paid by the customer regardless of how much power they use, or when they are used.

TVA is Taking Control Away from Its Customers

In 2018, TVA residential customers will pay an average fee of $17.16 per month, up from $11.44 in 2011. From 2011 to 2016 (most recent data available), the average price charged for actually using electricity also increased by about 1%, to an average annual price of 9.3 cents per kilowatt-hour. In 2018, the 50% increase in mandatory fees means that TVA’s local power companies will collect over $300 million more per year in fees than they did in 2011.

These unavoidable charges make it harder for any small power customer to save money, and higher mandatory fees make it particularly difficult for TVA’s low-income, minority and other customers with fixed incomes to control their electric bills.

The National Association of State Utility Consumer Advocates opposes the increased use of mandatory fees because they “disproportionately and inequitably increased the rates of low usage customers, a group that often includes low-income, elderly and minority customers.” The resolution explains that elderly people, lower-income households, and non-white people tend to use less electricity, and goes on to say:

Increasing the fixed, customer charge through the imposition of … high customer charge structures creates disproportionate impacts on low-volume consumers within a rate class, such that the lowest users of gas and electric service shoulder the highest percentage of rate increases, and the highest users of utility service experience lower-than-average rate increases, and even rate decreases…. Given these documented usage patterns, the imposition of high customer charge … rates unjustly shifts costs and disproportionately harms low-income, elderly, and minority ratepayers, in addition to low-users of gas and electric utility service in general.

As TVA’s local power companies shift residential customer rates from a metered rate (per kWh) to emphasize the mandatory fee (per month), customers have less of a financial incentive to save energy. A utility that collects $20 per month regardless of energy use, for example, can take away as much as 25% of the benefit of saving energy. For example, if a typical household reduces their energy use by 20% (with energy efficiency or by producing its own power from rooftop solar), that 20% energy savings would result in only about 15% bill savings after the mandatory fee is added back in.

The reduced incentive to save energy can translate into a significant increase in customer demand: over time, about 2%. For comparison, currently the Tennessee Valley Authority is spending millions of dollars to help customers reduce energy bills, and achieving an annual reduction of 0.2 % in energy demand. Utilities like KUB that have increased their mandatory fees by $10 or more per month have effectively wiped out about 10 years worth of residential energy efficiency program accomplishments.

Mandatory Fee Increases: Hiding in Plain View

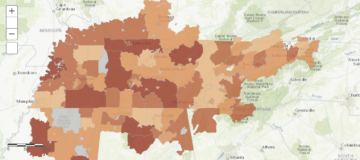

KUB is just one of 154 cooperative and municipal utilities who are both customers of and regulated by TVA. In 2011, KUB publicly explained that it was going to use mandatory fees to adapt to TVA’s new rate structures. Its “basic service” fee is disclosed on the KUB website and on customer bills. Yet many of the at least 86 local power companies that have adopted fee increases of 20% or greater are not so transparent.

For example, Memphis Light Gas and Water (MLGW) does not disclose its $11.60 per month mandatory fee on customer bills (see image at right). Neither has MLGW been very public with its plans to increase the mandatory fee.

In November 2017, MLGW prepared a proposal to increase the fee by $1 per month for residential customers as part of an overall 7.1% rate increase. In the draft council resolution prepared to endorse the overall rate, this rate increase was described as “a compound annual growth rate of 2.3% in the electric sales revenue over the three-year period 2018-2020 and a revenue neutral increase in fixed cost recovery and reduction in variable cost recovery for RS and RS-TOU rates.” Got that?

MLGW’s proposal to increase the fee by $1 per month was not mentioned in the draft resolution. Instead, it is buried near the back of a 379 page budget document provided to the Memphis City Council. That document also showed that the “reduction in variable cost recovery” did not actually mean a decrease in rates: As illustrated below, in addition to the increase in mandatory fees, electric rates were also proposed to increase by about 4%.

MLGW’s proposed rate increase was communicated following practices used by most utilities across the TVA region. Increases in mandatory fees are described as “revenue neutral,” even when overall electricity prices are trending upwards. This double-talk is characteristic of the “favor the big guy at the expense of the little guy” approach that is increasingly favored by TVA and many large, for-profit utilities.

Certainly there are exceptions. Athens Utility Board (as discussed in an earlier blog), KUB, and some other utilities do publicly share what they are doing, and why, with their customers. But MLGW and many others do not.

For example, Middle Tennessee Electric Membership Cooperative (MTEMC) operated with a mandatory fee of $9.79 per month in 2011, but today, residential customers pay $19.75 per month. MTEMC’s CEO Chris Jones recently boasted that his customers “not only enjoy rates 20 percent below the national average, they also have a voice in how their cooperative is run through their elected Board of Directors.” While MTEMC touts “rates 20 percent below,” its press releases, blogs, and newsletters are strangely silent on why its mandatory fee is above the national average.

Other utilities can be even more extreme. In response to a SACE consultant’s call requesting information on rates, Warren Rural Electric Cooperative Corporation (Warren RECC) refused, stating that historical rate information was not available to the public. Our consultant had similar conversations with staff at Gibson Electric Membership Corporation, Plateau Electric Cooperative, and Dysersburg Electric System. Dyersburg is also one of 31 municipal and cooperative utilities that do not appear to make residential rates available on a website.

Ultimately, the problem with the lack of transparency is being driven by TVA. TVA is the “retail rate regulator” for 150 of its local power companies, and also has “non-discriminatory oversight” over the other 4 companies.

But what does TVA’s regulatory oversight mean? For a regulator, TVA is remarkably secretive. TVA provides no disclosure as to what rates it has approved, how it approves them, or what standards it applies in setting those rates.

SACE is concerned that TVA has approved large increases in mandatory fees at roughly three-quarters of the local power companies it represents. By choosing to use fees to cover revenue, the utilities have reduced customers’ ability to take control over their bills by saving energy or choosing to generate their own solar power. But even if you do not share those concerns, you should be concerned that TVA can effectively regulate public power utilities – who are also its customers – without any oversight, or even any disclosure of its practices.