Today, the Trump EPA released its final Affordable Clean Energy (ACE) regulation to replace the Obama-era Clean Power Plan (CPP). Both rules regulate CO2 emissions from existing coal and gas power plants, but the similarities stop there. I spent over 3 years developing specific expertise in the now-defunct CPP to become the “CPP expert” at a global firm of ~450 energy consultants, and this is possibly the last chance I’ll get to make use of that now-obsolete knowledge, so here goes.

How did we get to the Clean Power Plan in the first place?

The day after President Obama announced his Climate Action Plan in June 2013, I was assigned to include the power plant piece of the policy in our firm’s energy price forecasting. The policy went through some iterations and so did our assumptions.

First came the draft Clean Power Plan in June 2014. There was plenty of pontificating about how easy/hard compliance with the rule would be, and how many costs/benefits the rule would generate. I went around to various conferences, met with clients in person and over the phone, and always the same question: will the regulation really happen? What will it look like in 5-10 years? 20-30 years? I even remember moderating a panel at a 2-day conference focused solely on the CPP while I was 8 months pregnant. Now that’s not a typical sight at an energy industry event!

I also distinctly remember the day the final CPP rule came out because it was in the middle of my maternity leave. My husband cared for our baby for a few days while I voraciously read through the final rule, the Regulatory Impact Analysis, and the technical documentation. My team and our clients needed my take on the rule, assumptions and methodologies needed to be updated, report text needed to be written.

Questions got wonkier. Would any state really choose a rate-based option? Would any state really choose to go it alone? How will states ultimately enforce this rule? Many of these complicated questions were being studied at SACE as well.

Why is the Clean Power Plan dead?

During the CPP heyday, there were always questions swirling about whether or not the CPP itself would ever become regulation, particularly because it was undergoing intense litigation and was stayed by the Supreme Court in an unprecedented move. Some states were more proactive, setting up processes to draft plans. Other states were banking on the CPP never becoming law, and unfortunately that move appears to have paid off.

Then, the day after the 2016 election, I updated all our models to remove any carbon regulation. We knew the CPP would never go into effect. It felt like a big change to the assumptions, but actually it didn’t change the output very much. Economics, not the CPP, was driving coal plants to retire and utilities to invest in wind and solar. Load still wasn’t recovering to pre-recession growth rates as many utilities expected.

In fact, when we look at the CPP targets today, they seem quaint for most parts of the country. The EIA’s latest Monthly Energy Review shows that 2018 CO2 emissions from the power sector are already 27% below 2005 levels and the EIA’s latest Annual Energy Outlook forecasts CO2 emissions from the power sector to be 33% below 2005 levels in 2030. The sum of the CPP state targets was 32% below 2005 levels by 2030. This is not a detailed look at CPP compliance, but it indicates that at least some parts of the country appear to be on track.

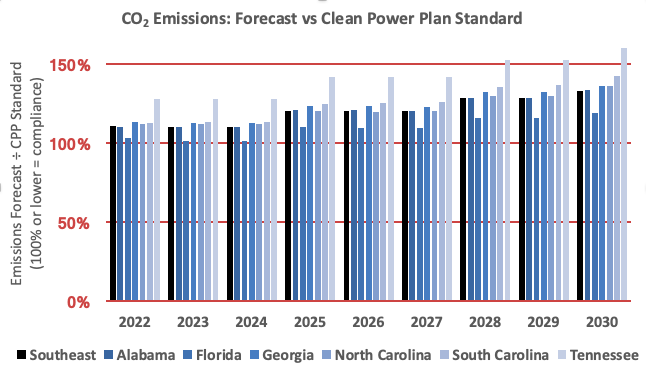

However, the Southeast is not yet on track to reduce emissions, even at the minimal rate called for in the Clean Power Plan. As shown below, Alabama, Florida, Georgia, North Carolina, South Carolina, and Tennessee would miss all of their CPP standards.

The federally-owned Tennessee Valley Authority is farthest away from CPP compliance of all the major Southeast utilities. Alabama Power, SCE&G, and Duke Energy Carolinas are also not doing so hot. Across much of the Southeast, there would be more pressure to develop clean energy and shift away from carbon pollution if the CPP had remained in effect. From this we can see that the CPP would have made a big difference in the Southeast, and residents of these states will suffer greater health and economic hardships as a result of its repeal.

The EPA is tasked with protecting health and welfare, and instead is protecting corporate profits.

I am outraged that an agency tasked with protecting the American people is using a finding that CO2 endangers public health and welfare so perversely. The proposed ACE not only rolls back the CPP, but it also a direct attack on a key provision of the Clean Air Act’s general protections of public health and welfare.

The proposed ACE would change what’s known as New Source Review (NSR), a Clean Air Act rule that requires plant owners that make a change that would significantly increase the plant’s annual emissions, then modern pollution controls must be installed. NSR ensures that older plants have to be brought up to modern standards instead of operating indefinitely with high pollution levels. Some highly polluting plants that were grandfathered into Clean Air Act regulations in the 1970s have put off investments so that they don’t trigger NSR.

The ACE proposes to change NSR so that it is triggered by increases in emission rates NOT increases in overall emissions. The emissions rate is related to total emissions by this formula:

Capacity (MW) x Capacity factor (%) x Emissions rate (tons/MWh) x 8,760 (hours/year) = Annual Emissions (tons)

[Note: the final ACE rule states that “the EPA is not taking final action on the proposed NSR reforms in this final rulemaking action; the EPA intends to take final action on that proposal in a separate final action at a later date.” (Final ACE rule, page 65)]

However, there are many plant upgrades that will make a plant more economical to operate without increasing the emissions rate. This will lead to to the older, higher polluting plant being run more often (increasing the capacity factor), and newer, less polluting plants being run less often. That means more smog, heavy metals, and particulate matter that lodges in our lungs and gives our kids asthma. This is really nasty stuff, guys.

This change to NSR could allow owners to extend the life of these pollution-spewing coal plants, many located right here in the Southeast. Energy Innovation’s recent study found 74% of US coal plants were more expensive to keep operating than replace with new wind and solar. I dug into their data and found that 86% of the coal capacity in the Southeast costs more to operate than replacing it with new wind and solar.

The ACE rule could lead to higher CO2 emissions.

Remember that formula for emissions two paragraphs up? Well, the ACE rule proposes that states set CO2 emission standards (in tons/MWh) for each existing plant based on heat-rate improvements, i.e. improvements to the plant’s efficiency so the plan gets more MWh out of each unit of fuel.

Efficiency improvements sound like a good thing, right? Well, improving the efficiency of these plants will also likely reduce their cost to operate and thus the utility will run the plant more, increasing the capacity factor. This is a phenomenon known as the emissions rebound effect (for a more detailed look see this analysis by Resources for the Future).

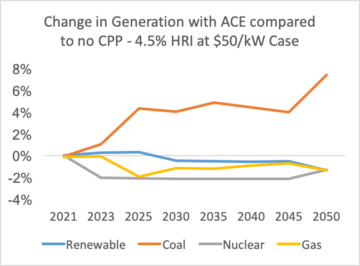

The EPA’s own analysis of the proposed ACE rule shows the ACE rule drives more generation from coal power plants and less from renewables, gas, and nuclear, as shown in the chart to the right. This leads to the finding that the ACE rule would lead to an additional 1,400 premature deaths per year when compared to the CPP. Instead of fixing the rule to reduce the actual number of premature deaths, the EPA is proposing to just ignore those premature deaths by changing the methodology.

What now?

Needless to say, I am approaching the release of the final ACE rule in a rather different way than the final CPP rule. Instead of being on maternity leave, I just celebrated my son’s 4th birthday. I have moved on from consulting to advocacy. Instead of wondering how the EPA could set up a cap-and-trade-style program for CO2 emissions, I’m worried about how far back the final ACE rule can really take us and how it will affect our children’s future.

The EPA received over 1.8 million comments on its CPP replacement docket, and we will see this week how many of those comments were in favor vs. opposition of the rule, and how the EPA used those comments when updating the proposed ACE to craft the final ACE rule.

I want to close with a shout-out to all my fellow CPP experts, particularly the current and former EPA employees, and everyone else who put hours of thought, analysis, argument, writing, blood, sweat, and tears into the Clean Power Plan. I see you. I’m with you. And while the CPP itself is a thing of the past, the effort that went into writing, analyzing, and arguing the CPP will make carbon policy across the US better in the future.