If there’s one thing you need to know about the Affordable Clean Energy (ACE) rule, the Trump Administration’s new proposal for limiting carbon emissions from power plants, it’s this: ACE was not designed to reduce emissions; ACE was designed to boost generation from coal plants.

Guest Blog | October 16, 2018 | Energy PolicyThis is a guest blog written by Julie McNamara with the Union for Concerned Scientists. The original blog can be viewed here.

If there’s one thing you need to know about the Affordable Clean Energy (ACE) rule, the Trump Administration’s new proposal for limiting carbon emissions from power plants, it’s this: ACE was not designed to reduce emissions; ACE was designed to boost generation from coal plants.

Which is audacious! A clean air standard that somehow manages to increase the nation’s use of its dirtiest power source, even when compared against a scenario with no carbon standards at all?

Remarkably, yes.

Because under the cover of establishing emissions guidelines, ACE is actually peddling regulatory work-arounds that aim to increase coal generation, a brazen attempt at stalling the industry’s precipitous decline.

How could something like this possibly come to pass from an agency whose core mission is to protect human health and the environment? A proposal that not only manages to increase emissions, but also worsens public health and raises costs?

Here, we’ll take a look.

With ACE, something is worse than nothing

ACE is the Trump Administration’s proposed replacement to the Clean Power Plan (CPP), a standard developed by the Obama Administration’s Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) to cut carbon pollution from power plants. Both ACE and the CPP are underpinned by the agency’s Endangerment and Cause or Contribute Findings, which necessitate that EPA regulate carbon emissions to protect human health and welfare.

Importantly, ACE doesn’t question the Endangerment Finding, nor EPA’s responsibility to act. Instead, this replacement reflects the fact that EPA’s current leadership believes—though will not allow the courts to decide—that the CPP exceeded the agency’s statutory authority, and thus that a far narrower approach to standard setting is appropriate instead.

Consequently, whereas the CPP had allowed achieving emissions reductions by letting cleaner plants run more—an efficiency made possible by the interconnected nature of the power system—the new proposal only considers emissions improvements from upgrades at individual coal plants.

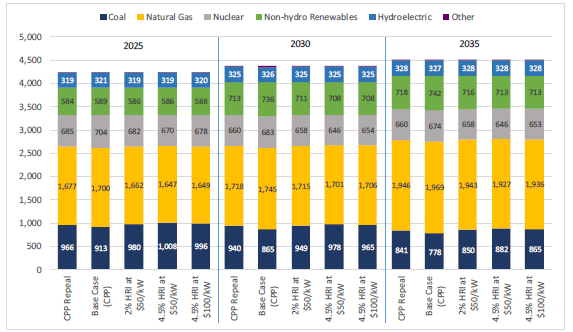

Specifically, EPA’s new analysis concludes that the only viable carbon emissions reductions from the power sector are heat-rate improvements (HRI) at select coal-fired power plants, resulting in emissions efficiency gains on the order of <1 to a few percent on a unit-by-unit basis. EPA projects that this approach would lead to total additional carbon dioxide emissions reductions of 0 to 1-2 percent compared to no policy at all.

But if only this proposal stopped at the point of being shamefully unambitious! At excluding improvements viable even within its unreasonably narrow approach, like co-firing cleaner fuels alongside coal, or deploying carbon capture and sequestration (CCS). At concluding that no reductions are viable at natural gas plants, even though their emissions present a major and growing challenge. At trying to do the absolute bare minimum to meet the agency’s statutory obligation to act.

If only, if only. But in fact, this feeble designation of the “best system of emissions reduction” (BSER) is only just the start.

Easing protections to boost coal

Alongside a dramatic weakening of the BSER, EPA advances two additional modifications that—though obscure—have the net effect of shifting ACE from impotent to unfortunately significant.

First, EPA proposes affording states wide latitude in determining whether their individual coal plants should pursue HRI, emphasizing extreme deference to states in the face of “source-specific factors.” As a result, even though EPA’s modeling allowed for coal plants to either make improvements or retire, almost certainly many units would choose the third option instead: keep running and change nothing. Which casts EPA’s projections of nearly negligible carbon emissions reductions from ACE into even more doubt.

But the stunning truth for the coal industry is that protecting plants from the costs of new regulations is still not enough to overcome its true existential threat: dismal economics compared to other energy sources.

And thus the second proposed change: an amendment to an EPA program called New Source Review (NSR).

NSR exists to protect the public from potentially significant increases in pollution from sites undertaking major construction projects, requiring those emitters that could trigger such increases to simultaneously upgrade their pollution controls.

Industry has repeatedly worked to eliminate NSR, balking at the potential costs of implementing new public health safeguards; however, these efforts have been repeatedly struck down by the courts. Now, EPA air chief Bill Wehrum is trying again.

The agency is proposing that if the hourly emissions rate of a plant doesn’t increase, it should be excused from NSR requirements. And the hourly rate won’t increase, because upgrades are specifically intended to improve them. But at an annual level? Well, if a plant incorporates a major efficiency upgrade, it’s likely to run a whole lot more as a result. Therefore, even though the hourlyemissions will not increase, the annual emissions will.

The result is a green light from EPA to sink major investment dollars into plants—regardless of pollution, regardless of payoff, and regardless of public health costs.

In ACE proposal, costs are high and benefits are low

And the upshot?

When the three tactics come together—an appallingly weak BSER, wide latitude afforded states to excuse plants from compliance, and work-arounds for NSR—we’re left with an emissions standard that is projected to increase coal generation even beyond that expected in a future with no carbon standard at all.

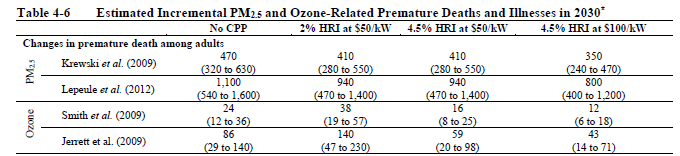

It’s unsurprising, then, that when compared against the CPP, ACE is projected to result in increased emissions and worse pollution, leading to more illnesses and even more premature deaths. EPA’s own analysis projects annual increases on the order of tens of thousands of asthma attacks and lost works days, and hundreds to up to 1,500 more deaths annually from changes in fine particulate matter and ozone alone.*

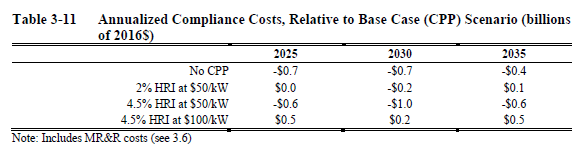

What’s more surprising, though, is that despite this administration’s continued rhetoric about the extreme burden of the CPP, the ACE proposal could—wait for it—actually cost more.

Because unlike the CPP, this proposal forces compliance on a plant-by-plant basis, meaning operators don’t have the option of turning to other resources to achieve far greater reductions at far lower costs. That myopic view of our integrated power sector is extremely economically inefficient.

Further, these cost comparisons are even less favorable for ACE than at first glance, because when EPA compared ACE against the CPP, it did not include energy efficiency as a possible CPP compliance mechanism and it did not include trading between states—two major opportunities for cost reductions. This means that in reality, the CPP likely would have cost even less, even though it would have achieved far more.

ACE deals the nation a losing hand

In releasing this proposal, Acting EPA Administrator Andrew Wheeler triumphantly declared that the agency would no longer be “picking winners and losers.”

Unfortunately, it appears his strategy is to just pick losers instead.

And that deals us all a losing hand. For our health, our environment, our savings, our future.

Because it’s hard to imagine a worse long-term investment than pumping hundreds of millions of dollars into old coal plants for net societal losses in the face of inevitable industry decline. But that’s the exact course that the Trump Administration’s EPA is trying to force our nation to take.

Indeed, the administration willfully ignores the fact that for effectively no upside, real communities will be left in the lurch for a long time to come, paying for misplaced investments with their wallets, and paying for worsened pollution with their lives.

* NOTE: In parallel rulemakings, EPA is working to: 1) restrict the use of scientific studies that let us ascertain such impacts, and 2) limit the degree to which such impacts will factor into future decision-making.