We explore how the ruling does - and does not - affect opportunities for climate action nationally and in the Southeast.

Cary Ritzler, Chris Carnevale, and Bryan Jacob | July 20, 2022 | Energy Policy, UtilitiesBrady Watson, former Civic Engagement Coordinator for the Southern Alliance for Clean Energy, also contributed to this blog post.

On Thursday, June 30th, 2022, the Supreme Court of the United States (SCOTUS) issued yet another landmark ruling, this time with consequences for climate, environmental protection, and federal regulations in general. The West Virginia vs. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) ruling specifically determines the method by which the EPA can set standards for regulating greenhouse gas emissions from existing power plants under one section of the Clean Air Act (CAA), but the majority opinion issued by the Court could result in the restriction of the EPA’s regulatory power, and even that of other federal agencies more broadly, through the “major questions” doctrine. In this article, we discuss the West Virginia vs. EPA Supreme Court ruling, and look at opportunities for climate action following the SCOTUS ruling.

West Virginia v. EPA and SCOTUS’ Ruling

When the DC Circuit Court of Appeals vacated a Trump-era power plant rule in January 2021, it also vacated the EPA’s repeal of the Obama-era Clean Power Plan (CPP), which was never actually implemented. Several organizations and states submitted a petition to appeal that decision, leading to the opinion by the Supreme Court in West Virginia v. EPA, released on June 30, 2022. While the case bears West Virginia’s name, the petition was co-submitted by several Southeast state attorneys general, including Chris Carr of Georgia and Alan Wilson of South Carolina.

The issue at hand in this case was not whether or not EPA has the authority to regulate greenhouse gas emissions from power plants, but rather how much latitude EPA has in exercising its established authority under Section 111 of the CAA. Specifically, the petitioners wanted the Supreme Court to rule on whether or not “generation shifting” (shifting electricity production from higher-polluting energy sources like coal to relatively cleaner sources like renewables at the grid level) is available to the EPA as a “best system of emission reduction” when it is setting emission standards under CAA Section 111. The petitioners argued that Congress did not explicitly allow the EPA to use this method to calculate emission standards, and rather characterized this method of implementing Section 111 as essentially EPA being too creative in interpreting and enacting the job Congress delegated to EPA. The petitioners also complained that EPA regulating in such a way exerted too much federal control over what is traditionally a state’s role of regulating electricity systems, that the federal government could not pick what technologies should supply power. The petitioners instead argued that EPA’s calculation of power plant emission standards under Section 111 should be limited to available onsite upgrades of technologies and procedures at specific power plants on an individual basis.

However, CAA Section 111(d) clearly states that EPA is to use the best system of emission reductions, whereas other parts of the CAA specify that EPA regulate based on the “best available control technology” or the “maximum achievable control technology.” EPA developed the CPP using generation shifting because it was following the guidance of section 111(d) and considering a system, not a technology.

SCOTUS’ decision on the case sided with the petitioners in stating that the EPA could not implement an emission standard based on generation shifting. Rather, the court decided that because EPA’s implementation of such a regulation would have widespread impacts, it falls under the “major questions doctrine” and the EPA must point to “clear congressional authorization” for the authority it claims. However, the court also did not entirely rule out the use of system-wide emissions reductions measures in future regulations – they kept their opinion limited to the CPP, stating that “the only interpretive question before us, and the only one we answer, is more narrow: whether the “best system of emission reduction” identified by EPA in the Clean Power Plan was within the authority granted to the Agency in Section 111(d) of the Clean Air Act.”

The Impacts of the Ruling on Clean Energy

The Supreme Court’s ruling in West Virginia comes as nationwide power sector carbon emissions are falling even in the absence of federal regulations on existing power plant greenhouse gas emissions. Power sector carbon emissions reductions have advanced primarily due to technological advancements and the favorable economics of cleaner energy sources. This trend has been apparent over the last decade-plus in the Southeast, as documented in SACE’s annual “Tracking Decarbonization in the Southeast” report series, which has shown progress, albeit slow, in decarbonization. The SCOTUS ruling will not directly affect this trajectory, but it could make picking up the pace of decarbonization in future years somewhat slower if future federal regulations are weaker than what might be issued in the absence of the ruling.

The direct impacts of the West Virginia v. EPA ruling on greenhouse gas regulation and climate policy more generally are fairly limited, though some legal experts warn that the precedent set by this case could have widespread impacts across various executive branch agencies.

SCOTUS’ ruling technically only applies to the CPP, an Obama-era regulation that never went into effect and never will. In fact, because of the modest carbon reduction goals of the CPP, they have already been surpassed even in the absence of the regulation. So there essentially is no direct effect of the ruling on existing climate policy. The ruling may affect future regulations, however, by threatening to limit the extent to which the Biden administration or other future administrations will seek to use system-wide generation shifting programs as measures to limit greenhouse gas emissions from existing power plants under the authority of Section 111. While the SCOTUS decision did not rule out using these types of programs in the future, future regulations under Section 111(d) will likely have to be careful in how they calculate emission standards in order to pass judicial muster.

The ruling also does not prohibit, but perhaps encourages, EPA to still be able to use 111(d) to mandate on-site upgrades to polluting power plants, such as carbon capture and sequestration or fuel-switching technologies should they be adequately commercialized. Furthermore, the ruling does not directly affect EPA’s authority to limit emissions from existing power plants using the authority of other sections of the CAA or other laws. In fact, in June of 2022 the EPA received a petition to regulate greenhouse gases (GHGs) under the Toxic Substances Control Act (TCSA), and has 90 days to respond to the petition. Regulation under TCSA could be harder for the current Supreme Court to overturn.

Broader Impacts of the Ruling

The implications of SCOTUS’ ruling get murkier – and perhaps more consequential – beyond the realm of Section 111(d) and the CPP. Because of the way the Court determined in this case that regulations that have major socioeconomic impacts need to have very specific authority and directions from Congress, West Virginia vs. EPA challenges the method of rulemaking that gives deference to federal agencies to construct regulations consistent with the delegation of responsibility from Congress. Such rulemaking processes are typical, where Congress passes laws and gives general guidance to the executive branch to carry out the laws, but leaves the nitty-gritty details to executive branch agencies like EPA that have expert staff to make rules that carry out the intent of Congress. However, the SCOTUS majority decision challenges this method by invoking the “major questions” doctrine, a belief that agencies (staffed by appointments or bureaucrats rather than elected officials) should not have the authority to decide on issues of major economic or political importance.

Climate Regulation Post West Virginia vs. EPA

The West Virginia v. EPA ruling upholds EPA’s authority to regulate GHGs under the CAA: EPA’s endangerment finding still imposes an obligation for EPA to protect Americans from the danger of GHGs. The ruling does not affect any standing regulations. However, for future regulations, the methods by which EPA enacts rules to regulate GHG emissions from power plants will be more limited as a result of the ruling. Also left untouched are EPA’s obligations to reduce other pollutants that harm public health or the environment, such as particulate matter, mercury, NOx, SOx, methane, and others. That said, the Court’s invocation of the major questions doctrine could generally hamper federal regulations to address the climate crisis, along with executive action on a range of issues.

However, federal regulation of pollutants is only one mechanism for acting on climate and clean energy, while policy from Congress, state and local governments, and corporations, as well as market forces and consumer preferences, remain potent enablers and drivers of our transition to clean energy. For example, expert analysis by Rhodium Group shows that federal GHG regulation on power plants is one of many tools in the toolkit to be used in achieving national climate goals by 2030.

Options Beyond Regulation

State and local policy are also critically important policy drivers for clean energy, as are future planning processes that are regulated by state-level commissions. As renewable energy has become a low-cost energy resource and technologies continue to be made more efficient, utility commissions’ responsibilities to ensure reasonable and prudent utility plans increasingly will necessarily encourage utilities to take advantage of cost-effective clean energy.

Congressional policy remains an important enabler of transitioning to clean energy, particularly here in the Southeast where state-level climate policy is largely absent and where we lack power markets so that economic forces can more quickly drive clean energy development. The House of Representatives passed a budget bill in November 2021 that would bend the curve on emissions, help communities transition to clean and renewable energy, and put our country on the path to achieving national climate and clean energy goals while directing 40% of climate benefits to disadvantaged communities. The budget bill has been stalled in the Senate over objections from Senator Joe Manchin, who recently said he would not support new spending on climate provisions at this time. However, since then, Sen. Manchin has stated he would be willing to revisit climate investments in the coming weeks. Congress should continue to prioritize action to guide investments in clean energy and set a clear direction for energy and climate policy for our nation.

The Dissent

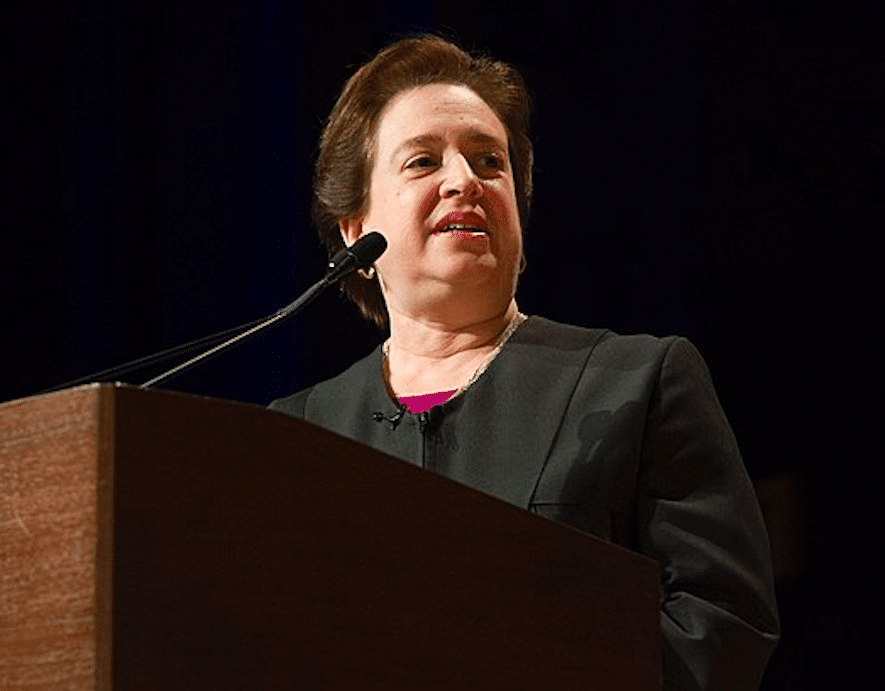

It is surprising and disappointing that the Supreme Court even felt compelled to consider this case since there is no active regulation to rule on. Justice Kagan points this out in her dissent, which was joined by Breyer and Sotomayor: “The Court today issues what is really an advisory opinion on the proper scope of the new rule EPA is considering. That new rule will be subject anyway to immediate, pre-enforcement judicial review. But this Court could not wait—even to see what the new rule says—to constrain EPA’s efforts to address climate change.” But since the ruling doesn’t impact any current rules, the near-term effects are muted. The ruling could have long-term implications for EPA’s regulation of power plant emissions. There remain many policy paths for our nation to eliminate fossil fuel pollution that the ruling does not touch, including regulatory pathways for EPA to facilitate reducing greenhouse gas emissions from power plants.

Justice Kagan’s dissent goes on to conclude that “The subject matter of the regulation here makes the Court’s intervention all the more troubling. Whatever else this Court may know about, it does not have a clue about how to address climate change. And let’s say the obvious: The stakes here are high. Yet the Court today prevents congressionally authorized agency action to curb power plants’ carbon dioxide emissions. The Court appoints itself—instead of Congress or the expert agency—the decision maker on climate policy. I cannot think of many things more frightening. Respectfully, I dissent.“