Climate science shows we must achieve net-zero GHG emissions between 2040-2055 to limit the global average temperature increase to 1.5 degrees C and avoid the worst impacts of the climate crisis.

Heather Pohnan and Maggie Shober | June 22, 2022 | Climate Change, Coal, Energy Policy, Fossil Gas, UtilitiesGlobal greenhouse gas emissions must peak by 2025, experience rapid and deep reductions, and reach net zero by the early 2050s to limit warming to 1.5 degrees C in order to avoid the worst impacts of the climate crisis. Many utilities and municipalities have acknowledged this dynamic, but the Southern Alliance for Clean Energy’s fourth annual “Tracking Decarbonization in the Southeast“ report highlights that current utility resource plans are not in line with this overarching target. Obstacles to getting utilities on track that are discussed in our report include: increasing reliance on fossil gas, underutilizing energy efficiency, and placing limitations on popular technologies such as rooftop solar. There’s still a lot of work to do before any Southeast utility is on track to decarbonize.

Why focus on decarbonizing the power sector specifically?

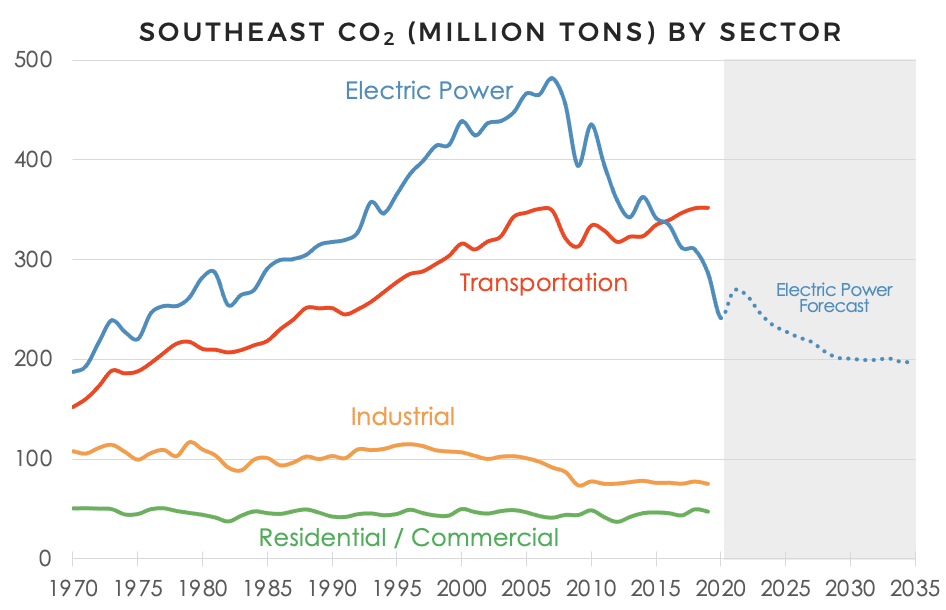

While emissions reduction opportunities exist in many different sectors, our report focuses on the decarbonization of the electric power sector of the Southeastern United States. Decarbonization is the transition of our power supply to sources that emit lower CO2 emissions, usually with the goal of using zero-carbon resources to power all sectors. Utilities can decarbonize by replacing fossil fuels with energy efficiency and energy from renewable sources. Other sectors can use a decarbonization strategy called electrification, which means switching from direct fossil fuel use to charging with electricity instead. For example, transportation emissions can be lowered by replacing vehicles that run on gasoline and diesel fuel to electric vehicles (EVs).

Decarbonizing the electric power sector holds great significance for utilities in the Southeast, as more consumers, businesses, and local governments are beginning to electrify. Power sector emissions have sharply fallen from their peak in 2007, to the point where the transportation sector is now the largest source of CO2 in the Southeast – a trend across most states and regions in the U.S. The fact that transportation has eclipsed the power sector does not diminish the importance of decarbonizing the power supply – it actually underscores it. When EVs are plugged in to charge, drivers are using utility-generated power for their transportation needs. Therefore, the cleaner the electricity, the cleaner the EV. In fact, decarbonization of the power sector is a critical tool to reduce emissions in all sectors through electrification.

How do we track decarbonization and why are we doing it?

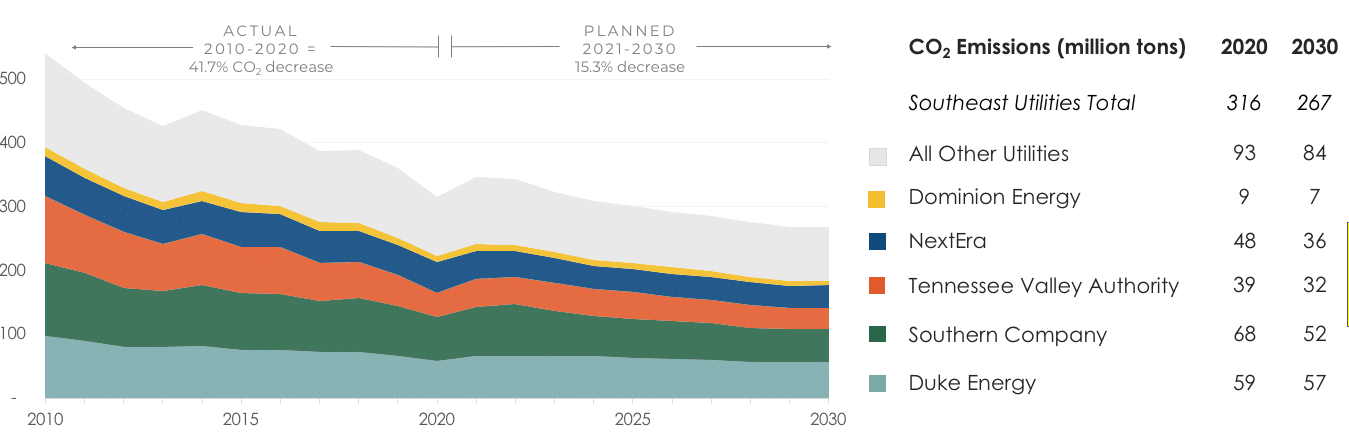

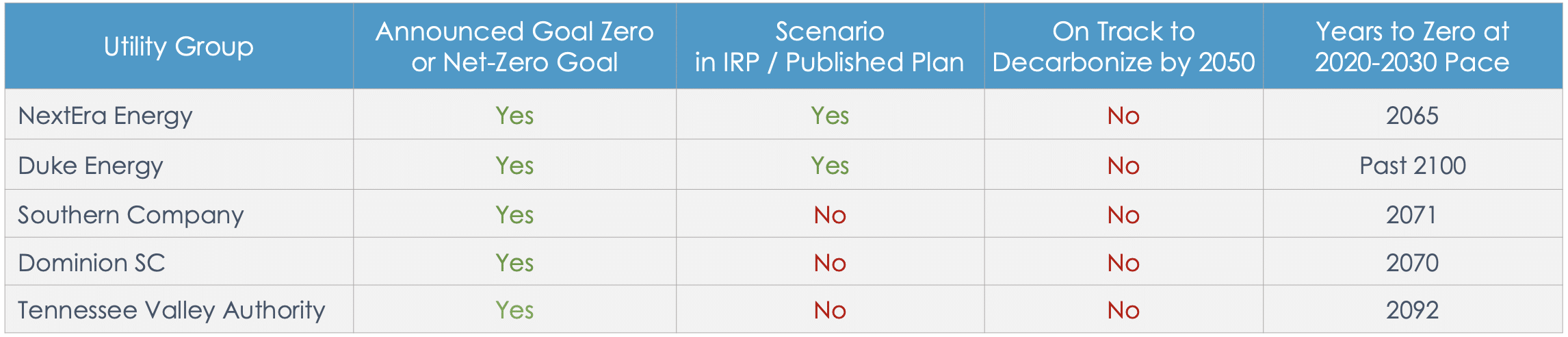

The Southeast is home to some of the largest utility systems in the nation, many of which have been in the national spotlight for their professed commitment to decarbonization. Duke Energy, Southern Company, Dominion, NextEra Energy, and the Tennessee Valley Authority (TVA) have all established decarbonization goals. Of these, the two largest CO2 emitters, Duke and Southern, have both made pledges to reach net-zero emissions by 2050, while NextEra recently set a target to get to zero without any carbon offsets by 2045. TVA has announced a series of coal retirements as part of its plan to reduce emissions 70% from 2005 levels by 2030 on the path to 80% by 2035 while saying it has an ‘aspiration’ to get to net-zero by 2050.

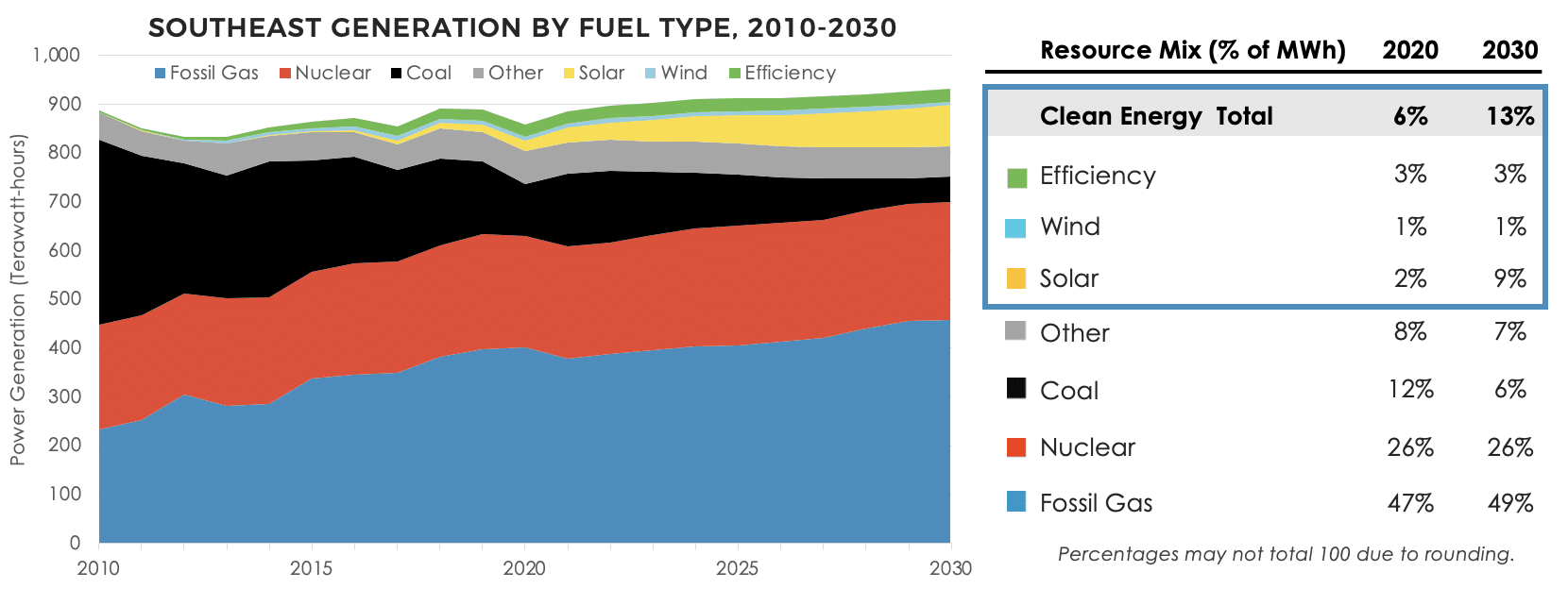

However, there are often inconsistencies between stated goals and resource plans. So how do we track the progress of these attempts? We look at the emissions associated with what utilities are planning to do, not just what goal they have set. Let’s start with the generation mix, or the mix of resources utilities use to meet generation needs. The mix of resources that utilities use for power is more critical than ever, especially when plans show that utilities are planning to continue heavy fossil fuel use in the future.

Current utility plans show that goals to decarbonize will be hindered by rising fossil gas consumption. Fossil gas plants are already fueling nearly half of the region’s total electric generation today, yet utilities plan to still increase reliance on gas generation in the coming years. Even utilities with zero-carbon goals such as Duke, Southern Company, and TVA are continuing to pursue fossil gas. This is troubling because utilities that are looking to decarbonize should not be making more long-term investments in fossil fuels that emit carbon. This is also troubling because the goal of decarbonization should be to switch to zero-carbon resources. When consumed, different fuels emit different amounts of carbon for each megawatt-hour (MWh) of electricity produced. This is known as carbon intensity, and it’s generally expressed in lbs of CO2/MWh. The carbon intensity of fossil gas plants is approximately half of coal plants, so during the past decade, utilities have generally switched from coal to gas. But even a utility or resource with a ‘lower’ carbon intensity can still contribute significantly when they are providing a large amount of electricity to a lot of customers, so it is important to look at who is contributing to total emissions.

Since complete decarbonization is needed to avoid the worst impacts of the climate crisis, it is important to also look at total emissions reductions. While the per megawatt-hour emissions intensity can be useful for quickly comparing fuel types or utilities against one another, it doesn’t necessarily tell us anything about how close a utility is to reaching zero. We see that a noticeable drop in 2020 due to the pandemic is still only a drop in the bucket when compared to the path to zero. Looking at how quickly absolute emissions reductions occur over longer timeframes gives us a window into just how long it will take to reach zero emissions based on the resource plans utilities have submitted to regulators.

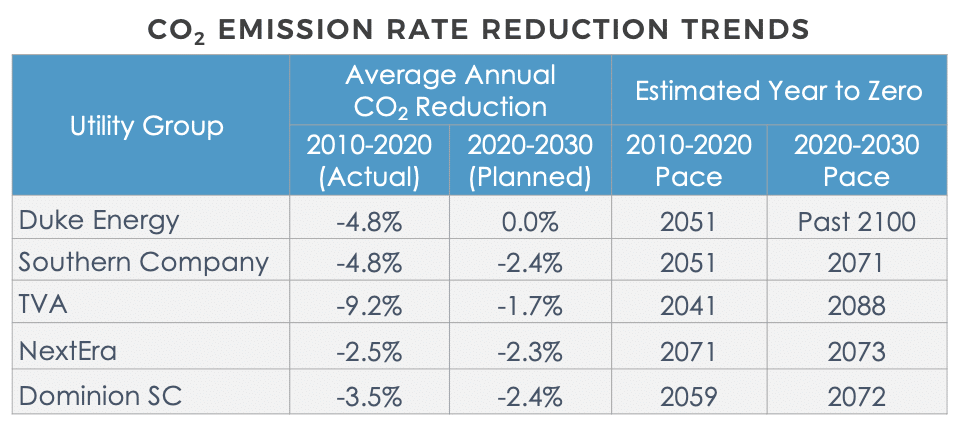

Most utilities were reducing carbon at a higher rate in the last decade than they plan to do in the coming decade. This is because most emission reductions from 2010-2020 were the result of flat or declining utility load paired with retiring coal generation and replacing it with fossil gas. Fossil gas is now the dominant fuel in the region, with many utilities still planning to add new gas infrastructure in the future. As a result, planned future reductions are occurring much slower than in the past decade and at a rate that would miss even the latest decarbonization “deadline” by several decades. For utilities to decarbonize at the pace seen in the 2010s they will have to retire remaining coal plants at a steady pace and replace fossil gas with clean, zero-carbon energy sources like wind, solar, storage, and energy efficiency.

What Utilities Say vs. What They Do

There’s a growing consensus from customers, investors, and regulators: everyone wants utilities to provide a carbon-free power supply. Utilities have begun catering to this want by publicizing emissions reductions and in some cases announcing decarbonization goals with various stylings (net-zero, low to no carbon, carbon-free). However, scientists have been clear that decarbonizing isn’t really a want, it’s a need. And it’s becoming increasingly clear that utilities’ actions are not meeting this need.

While many electric utilities are eager to make it known they’ve reduced emissions in the past, fewer have announced a goal that takes scientific guidance into consideration. Notably, TVA tends to tout its emission reductions over the last 10-15 years without laying concrete plans to continue to reduce emissions at that same rate. Only one utility, Duke’s two subsidiaries in the Carolinas, has taken the step to include its net-zero decarbonization goal in its Integrated Resource Planning (IRP), or long-term energy resource, planning process (though even that can fall short in some areas) and based on current resource plans, none are on track to decarbonize by 2035, 2040, or even 2050. When announcing its goal to achieve zero emissions by 2045, NextEra laid out a set of interim targets and high-level generation mixes for its regulated utility FPL. This is a step in the right direction, and we look forward to working with FPL and Florida regulators on the details for achieving this goal in an equitable manner, such as through the inclusion of energy efficiency.

What’s at stake? What next?

As we’ve said in the past, every year matters, and every choice matters when it comes to acting on climate change. Delaying further decarbonization until the next year, or the next IRP cycle or the next decade is too risky for residents of a region expected to feel the impacts of climate change first and worst. The Southeast is home to many frontline communities that are already being negatively affected by fossil fuels and the climate crisis. Stronger and more frequent extreme weather events, coastal flooding, poor air quality, and unpredictable energy prices are likely to continue to harm our communities.

Although it is difficult to fully represent the relationship between delayed climate action and all impacts, it is possible to look at the increased cost of failing to act. Namely, that weather disaster are expected to become more frequent and intense due to climate change. In the last five years, the U.S. has averaged at least $148.4 billion dollars worth of weather and climate damage each year. But likely more, as NOAA mainly catalogs climate and weather disasters that cost one billion or more dollars. Smaller disasters, and costs associated with resulting health care needs from these events, are not included. If that $148.4 billion is spread out evenly across the year, that means the cost of inaction would increase by $4,706 every second. To see what that looks like, a cost of inaction tracker shows why climate action can’t wait.

With so much at stake, what is the region to do? Although SACE primarily intervenes in state-level utility regulation and contends that utility resource planning is one of the best opportunities to put decarbonization goals into practice, we can still see that action is not happening fast enough. Engaging on multiple levels, including federally is necessary for concerned citizens.

Take Action: Urge Your Members of Congress to Take Climate Action