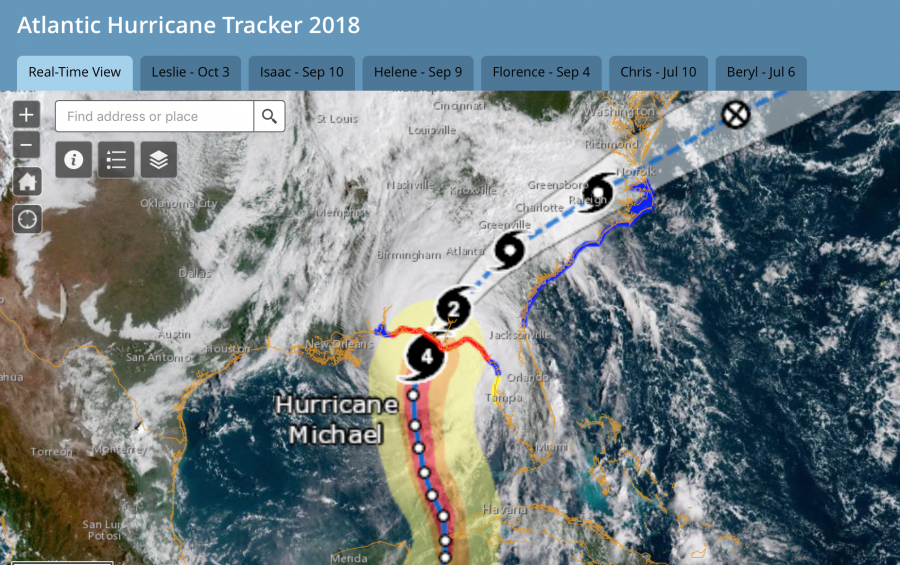

It’s hard to believe we are writing another blog about another big hurricane headed towards the Southeast not even a month after Hurricane Florence struck the Carolinas. But we are! If you are in the path of Hurricane Michael, here are tips to stay safe from the Department of Homeland Security.

Guest Blog | October 10, 2018 | Climate Change, Extreme WeatherChris Carnevale with SACE contributed to this blog post.

It’s hard to believe we are writing another blog about another big hurricane headed towards the Southeast not even a month after Hurricane Florence struck the Carolinas. But we are! If you are in the path of Hurricane Michael, here are tips to stay safe from the Department of Homeland Security. As we mentioned in our pre-Hurricane Florence blog, we must keep talking about preparing longer term for hurricanes in a warmer world.

First, it needs to be said that hurricanes are not caused by climate change. However, it’s also important to understand that the impacts of hurricanes are very much influenced by a warming climate. NOAA states that the average temperature for September 2018 across the contiguous U.S. coming was 67.8 degrees F (2.9 degrees above average), making it the fourth hottest September in the 124-year record. Let’s take a deeper dive on the links are between hurricanes and climate change.

Earlier this year, SACE hosted a webinar with NASA Senior Scientist Timothy Hall, who discussed the effects of climate change on hurricanes, outlining five effects, shown in the graphic below in order from more certain to less certain.

The most certain effect of global warming on hurricanes is that the sea level rise gives storm surge significantly more flooding potential. When tropical storms or hurricanes arrive onshore, they push water inland, raising the sea level often multiple feet. As the sea rises from higher temperatures, each storm pushes flood waters higher than it would have without sea level rise. For example, insurance giant Lloyds of London estimated that about 30 percent of the New York City area losses from Hurricane Sandy were attributable to just the historical observed sea level rise of about 8 inches. In recent years, the rate of sea level rise has doubled or tripled from human-caused global warming, and it is expected that global sea levels will rise 1 to 4 feet–but as much as 8 feet–over the course of this century, depending on how swiftly carbon pollution is reduced.

Additionally, as the air warms due to greenhouse gas pollution, it is capable of holding more moisture and therefore hurricanes have the potential to release greater amounts of rain, in turn causing greater flooding. NASA scientist William Lau found that precipitation from tropical cyclones increased 24 percent per decade from 1988 to 2012. A recent illustration of this increased precipitation potential of hurricanes was found in Hurricane Harvey last year, when about 20 percent of the rainfall that plagued the region is attributed to warming that has already occurred in the Gulf of Mexico.

Meanwhile, as oceans warm, the growing differential between the warmer ocean water and cooler atmospheric air is raising the intensity potential of hurricanes, which can be thought of as their “speed limit.” As this “speed limit” increases, we may see an increase in the frequency of category 4 and 5 hurricanes in the future, and some storms may surpass the intensity of any hurricanes that have ever been measured before. An interesting point is that the overall frequency of all hurricanes (categories 1-5) may decline in the future even as the average strength of the hurricanes increases.

Hurricanes Florence and Michael are a huge wake up calls that coastal residents need to be prepared for worst-case scenarios throughout the hurricane season. And just as we prepare our households for disasters in the short-term with things like having water, food, flashlights, and an evacuation plan–we must also prepare our communities to avert worst-cases in the long-term by reducing carbon pollution.